This post is co-authored by Jake Duncan, Senior Associate at IMT and Dr. Robert Klee, Lecturer at Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and a collaborator on the Decarbonization Accelerator.

As climate change takes on increased importance and urgency, so do the frameworks guiding leaders and decision makers. Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) are critical players in the power sector and, therefore, on issues related to energy and carbon emissions. The laws and statues that define the Commission’s role, decades old and buried deep within a state’s administrative rules, are the foundation on which they serve and make decisions. To accelerate climate change mitigation and a more equitable economic transition, we need to address the framework by which Public Utility Commissions regulate our nation’s utilities.

What are Public Utility Commissions and Why Does Their Mandate Matter?

Public Utility Commissions (PUCs, also called Public Service Commissions or similar names) are the state agencies that regulate investor-owned utilities for the public good. In the early 1900’s, both the public and private sectors agreed to grant monopoly rights to utilities, who, in exchange, agreed to a regulatory compact (see figure 1). PUCs exist to make sure that utility investments are reasonable, that utilities maintain reliable service, and that they can maintain a viable business. Rightly so, PUCs have historically had a narrow focus on affordability, safety, and reliability.

Now, however, utilities are increasingly being asked to invest heavily in renewable energy, energy efficiency, storage, and new technologies so that jurisdictions can meet climate goals. This puts utilities in a bit of a bind. Not only does it go against the traditional utility business model that has been around for 100 years but even if a utility wants to change the way it operates, it can be hard to get regulatory approval. Advocates such as city governments can have an impact by contributing to the regulatory process, but even if regulators personally want to promote clean energy and climate action, that is not an explicit part of their role.

It is time to redefine the PUC regulators’ role. Let’s empower Public Utility Commissions to be part of the climate solution.

Redesigning PUCs for the 21st Century

A number of jurisdictions, including Washington, DC, and Connecticut, are expanding their PUC’s mandate to consider the impacts of climate change and their state’s climate goals in the PUC’s decision making. This relatively simple action can have a tremendous long-term impact because it changes the utility regulatory framework and introduces more sustainable decision making throughout the clean energy transition.

DC’s Climate Goals Become Embedded in the City’s Public Service Utility

The District of Columbia has been an early mover in many climate and energy policies, due in part its unique government structure with its own Public Service Commission (PSC), appointed by the Mayor and operating with the advice and consent of the District Council. In 2008, the District passed the Clean and Affordable Energy Act, which, among other clean energy actions, directed the PSC to “consider the preservation of environmental quality” in its decision making. However, greenhouse gas emissions were not considered part of the “environmental quality” definition, and this provision could not be used to push for more renewables or energy efficiency.

However, in 2018, the District passed the Clean Energy Omnibus Act. This landmark legislation got national attention as it created the nation’s first Building Performance Standard and raised the District’s Renewable Portfolio Standard to 100%. This time, Councilmember Mary Cheh’s office included a more specific provision for the PSC, directing it to consider,

“… the preservation of environmental quality, including effects on global climate change and the District’s public climate commitments” (emphasis added).

The impact of the change was immediate; the PSC and stakeholders referenced the new, expanded mandate in cases and hearings, even before the legislation came into effect in March 2019.

The Clean Energy Omnibus Act also gave the same directive to District’s Office of the People’s Council (OPC), a public agency that represents ratepayers in every PSC proceeding. A consistent voice for ratepayers in utility proceedings, the OPC will now consider the climate change impacts of new policies and projects alongside its longstanding commitment to support consumers’ rights to safe, affordable, reliable energy.

The effects of the legislation are clearly illustrated in cases related to gas subsidies for Washington Gas & Light (WGL), a local gas utility that serves the District and parts of Maryland. In Maryland, WGL received approval from the Maryland PSC for an indirect subsidy to put gas hookups in new buildings. In 2017, WGL requested approval from the DC PSC for a similar subsidy for its DC service area. The PSC decided to run the program as a three-year pilot to test the economics of the program, as the PSC’s only considerations at the time were the program’s impact on affordability, reliability, and economics. In a 2019 rate case, WGL applied to extend the pilot another two years. However, by then the new environmental mandate was in effect. The result? The OPC and other stakeholders, including the DC City Government and the Sierra Club, argued that the project was in opposition to the city’s climate emissions reduction and electrification goals, and the PSC denied the request, specifically citing its new mandate as a cause.

Connecticut Ties PUC Decision Making to Climate-focused Energy Strategies and Plans

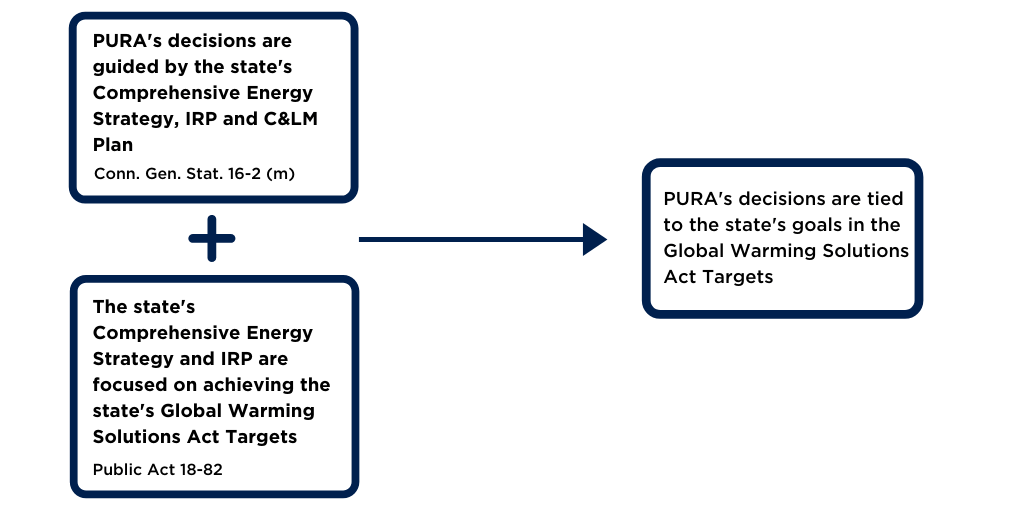

Connecticut, another leading state on climate action, enacted the same concept in a different manner. Connecticut’s utility commission–the Public Utility Regulatory Authority (PURA)–is directed to consider climate change through two statutory steps.

In Connecticut, PURA’s decisions are statutorily guided by the state’s energy strategies and plans (Conn. Gen. Stat. 16-2(m)), which include:

- the state’s Comprehensive Energy Strategy (Conn. Gen. Stat. 16-3d), which assesses all of the energy needs of the state, including electricity, heating, cooling, and transportation every four years;

- the state’s Integrated Resources Plan (IRP) (Conn. Gen. Stat. 16-3a), which assesses the state’s electric energy and capacity requirements over three, five, and ten years; and

- the state’s Conservation and Load Management Plan (C&LM) (Conn. Gen. Stat. 16-245m), which implements electric and gas energy conservation programs according to a three-year plan.

As part of a comprehensive 2018 climate bill (Public Act 18-82), Connecticut’s legislature required the Comprehensive Energy Strategy and the IRP to focus on how Connecticut will achieve its binding climate targets in its Global Warming Solutions Act (Conn. Gen. Stat. 22a-200a). That same climate bill also required the Comprehensive Energy Strategy to ensure that the state’s energy efficiency goals are met. In this manner, the legislature linked the state’s major energy strategies and plans to the state’s greenhouse gas reduction targets. (The comprehensive 2018 climate bill also strengthened the state’s targets by adding a new 45% economy-wide greenhouse gas reduction target for 2030.)

Although perhaps not as straightforward as DC’s direct approach to updating the utility mandate, as shown in the graphic below, a two-step process effectively embeds Connecticut’s climate targets into PURA’s decision-making framework. But, like what is happening in DC, the shift in focus towards achieving climate targets in Connecticut is already expanding the conversation between utilities and PURA to include more carbon-saving options.

For example, PURA recently opened a grid modernization proceeding, which focuses on how the state will update its energy infrastructure to accommodate renewables and smart technology while increasing resilience and reliability. The objectives of the grid modernization proceeding include “remov[ing] the barriers to growth of the burgeoning Connecticut green economy,” and “enabl[ing] an economy-wide transition to a decarbonized future.” This language is unprecedented.

PURA’s utility regulatory proceeding will now break down regulatory barriers and promote decarbonization through building and transportation electrification, storage, and other distributed energy resources – all common objectives of climate and clean energy advocates in the public and private sectors. This shift in PURA’s focus, found in language throughout its grid modernization proceeding, would not have been possible without the statutory shifts that required PURA to be guided by the state’s climate targets, and enlisted PURA’s help in achieving those targets.

Fundamental Shifts in Utility Governance are Key to Progress on Climate Change

Changing the guiding mandate for utilities is a comparatively simple solution for advancing decarbonization in the power sector, and the idea is catching on. While DC’s approach is more straightforward than Connecticut’s, Connecticut’s method does enable (and require) more inter-department coordination. States interested in expanding their PUC’s mandate should consider both options, as well as how this approach can be tailored to meet other social priorities.

This strategy is catching on. Maryland has a pending bill that follows the DC model, and includes a new provision to ensure a fair labor transition. Washington State’s recent clean energy law recognizes the important role utilities will play in the clean energy transition, and that their PUC’s authority should be expanded to include flexible regulatory mechanisms to achieve that clean energy transition.

In addition to or independent of expanding the PUC’s charter to consider state climate goals, 11 states have directed their PUCs to develop a social cost of carbon metric. This process assigns a cost to carbon emissions that utilities have to factor into their analyses and proposals. While this approach does not explicitly direct the PUC to work to achieve state goals, it does bring the cost of greenhouse gas emissions into the traditional PUC economic regulatory framework and can play a role in pipeline approval, low-emission vehicle programs, energy planning, and more.

As states look for mechanisms to deliver on the growing wave of carbon and renewable energy commitments, altering the PUC mandate is a lesser-known but highly effective, no cost, and immediate solution. This promising approach offers a powerful way to put climate plans into action and transform our energy grid. IMT encourages state and local governments to view PUCs as partners in their climate plans and to consider legislative language that allows and encourages PUCs to include environmental impact in their decision making. We welcome feedback on how your community is connecting to utilities to address climate and clean energy goals. Write to imtweb@imt.org to share your thoughts.